Orchards in America

The text of this page is taken from Fruitful Legacy: A Historic Context of Orchards in the United States, by Susan A. Dolan, 2009. The full volume can be viewed both online and in the Ralston Cider Mill’s library collection.

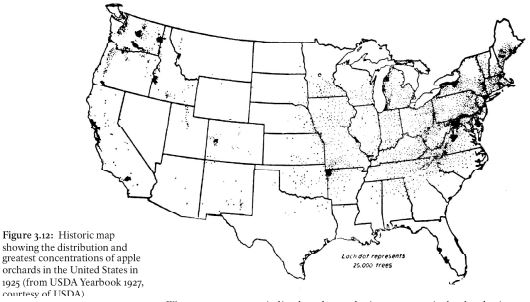

Each dot represents 25,000 trees.

According to the National Park Service, the history of orchards in the United States can be organized into four distinct periods:

- 1600-1800, when European fruit trees were introduced and planted for both subsistence farming and pleasure.

- 1801-1880, when collectors and entrepreneurs developed fruit varieties.

- 1881-1945, when orchard development focused on commercialization, technology, and regionalism.

- 1946-present, when orchard production intensified and dwarf trees became commonplace.

1600-1800

For the first 200 years of settlement in America, the fruits of farm orchards were used almost exclusively for making alcoholic beverages and feeding livestock. Farm orchards lacked a regular geometry, as they were sown, rather than planted out, and consisted of wild-looking, unpruned trees, with very tall trunks, greater than six feet. Lower limbs were browsed off by livestock or wildlife. Apples were grown primarily for cider.

In colonial America the most important beverage was cider. The importance can hardly be overstated, as cider was both the beverage of subsistence, before potable water, and a commodity for trade. Hard cider was a staple for all classes of Americans and a form of currency for goods and services. A five-acre farm orchard of seed-grown or seedling apple trees could yield more than 1,000 gallons of cider per year. Cider could be kept throughout the winter and spring in cold cellars.

Although seedling apples were generally not eaten raw because of their taste, they had many culinary uses and were extensively used in baking and drying. Some seedling fruit trees, including seedling apple trees, did produce pleasantly edible fruits, though in general, the edibility of their fruits was considered very unreliable.

1801-1880

From 1801-1870, many thousands of true varieties of fruits were planted. Many farmers in the east had converted their fields from cereal grains and vegetables to orchards, and by this time most orchard fruits were grown for human consumption as fresh fruit. Other commodities were replacing the use of seedling fruits for cider and livestock feed.

In the West, many newly claimed lands were immediately developed as commercial orchards. Orchards were laid out with relatively wide spacing between trees, typically 30 feet square for apple trees. The trees were grafted close to the ground and were allowed to develop tall trunks. A typical orchard tree had a large, unpruned canopy, and without fruit thinning by the orchardist, would bear a good crop only every other year.

Dwarf apple and pear trees were available through the nursery trade, which had spread to every larger city in the country. However, dwarf trees were generally found only in fruit gardens, which remained distinct from farm orchards or commercial orchards. Seedling fruit trees were still being sown in the newly settled West, though even the most remote farm orchards were typically laid out with a handful of true varieties in addition to seedling trees, to provide some good fresh fruit.

1881-1945

The evolution of orchards from 1881 to 1945 was fueled by technological and scientific discovery, and led to the professional and commercial development of the orchard industry. The most important changes from a cultural resource management perspective were transformations in the form, shape, and layout of orchard trees, and a dramatic reduction in the number of varieties grown.

Orchard tree form changed from a five-foot-tall trunk to a less than three foot-tall trunk, and orchard layout was expanded to greater spacing. The layout changes were made for greater access for new machinery and equipment and to increase the yield from mature trees. The dramatic decrease in the number of varieties grown was due to a process of selection for commercial fitness. At the end of the period, most orchard fruit species were represented by just 10 widely grown commercial varieties. For apple, Baldwin and Ben Davis were the most important commercial varieties in the early 20th century, but were rapidly superseded by McIntosh for Baldwin and Red Delicious for Ben Davis.

The development of Red Delicious during this period had an enormous impact on apple growing, resulting in greater profitability for the industry, great fashionability of red apples, greater ubiquity of a single variety, and further obsolescence of superseded varieties.

The number of fruit trees and orchards fell dramatically during the period, with all but the West Coast losing orchards to increasing urbanization. Approximately 50 percent of the fruit trees that existed in 1880 were gone by 1930, though the great paring down in the number of orchards was paralleled by a rise in specialized, commercial orchards, managed by growers rather than farmers. Technologies that buoyed the development of commercial orchards included a nationwide network of railroads and then later a national system of roads, growth in canning technology and irrigation systems, and the discovery of mechanical refrigeration and cold storage. Scientific breakthroughs included the discovery of disease organisms and the development of the first pesticides for orchard pest control.

1945-Present

The trend towards higher density, dwarf fruit tree orchards in the period from World War II to the present was fueled by the need to lower costs of production in an increasingly competitive marketplace. The discovery by European researchers that select dwarfing rootstocks could produce greater yields of higher quality fruit than seedling rootstocks led to the development of clonal dwarfing rootstocks. First developed for apple before World War II, clonal dwarfing rootstocks were then created for pear, plum, cherry, apricot, and citrus. These rootstocks provided multiple benefits for growers, including more quality fruit per unit of wood production, earlier fruit bearing, disease resistance, and easier orchard management.

By the 1960s, clonal rootstocks had been adopted for apple orchards throughout the United States. Accompanying the use of clonal dwarfing rootstocks was the adoption of high-density management systems, using trellises to grow dwarf spindle trees at 2-5 x 6-10 feet spacing (1,000 to 2,000 trees per acre). Gradually, the movement towards higher density management systems affected all orchard fruits that would be hand-picked for the fresh market.

Development in the 1960s of Controlled Atmosphere storage fueled the overproduction of Red and Golden Delicious apple varieties. Their ultimate loss in popularity and value in the 1980s was a response to new global competition. New varieties and new imports devalued Red and Golden Delicious and stimulated a trend towards the growing of a broader range of new apple varieties.

At the turn of the 21st century, global market forces are shaping the work of orchardists and horticultural researchers. New orchards will be grown on clonal dwarfing rootstocks in high-density management systems, which will produce the greatest quantity of highest quality fruit for the majority of the 10-year life span of the orchard. These new rotational orchards are planned to keep pace with the concept of variety obsolescence.

As a result of the trends in orchard history since World War II, earlier orchards with widely spaced trees on seedling rootstocks have come to represent archaic horticulture. Thousands of varieties have been lost as a result of the decreased number of varieties grown. These changes have distinguished the older orchards in national parks dating prior to World War II, which represent earlier periods in the history of American horticulture. Historic orchards in national parks and elsewhere are now the repositories of rare varieties or strains of varieties, and are becoming rare examples of extant old fruit tree forms and layouts. Orchards have changed radically since World War II, and the rate of change can be expected to continue to grow.