Technology

Between its construction in 1848 and its closure in 1938, the mill structure operated as a gristmill, cider mill, and distillery. Remnants of each of these functions can still be observed in the mill and around the grounds. The mill has been home to a remarkable variety of technology spanning early and modern industry, and the Ralston Cider Mill is one of only a few sites where visitors can observe original equipment in operation.

Cider Mill

Shafts, Belts, and Pulleys

Running from the belowground turbine casing in the lower level to the roof rafters on the fourth floor, one main vertical shaft powers all of the machinery inside and outside the mill. Belts connect horizontal jack shafts and line shafts to the main shaft, and additional belts connect the machines to the horizontal shafts. Visitors to the mill will notice belts and pulleys of various sizes and materials, all working simultaneously in concert.

Knuckle-Joint Press

Dating from the 1870s, the Boomer & Boschert knuckle-joint model is the older of the Ralston Cider Mill’s two cider presses. The imposing 12-foot wood and metal press was likely located at the Thompson Distillery on Hilltop Road in Mendham prior to being moved into the Ralston Cider Mill around 1910. Visitors to the mill can see the intricate hand-painted detail work up close and observe this 150-year-old machine in action.

Gear Press

The “newer” of the Ralston Cider Mill’s presses, the Boomer & Boschert power screw press is made from steel beams. Its gears enable the machine to operate in three speeds up and down, making this press far more efficient than the older knuckle-joint press. At full capacity, this press can produce several thousand gallons of cider per day.

Turbine

In the second half of the 19th century, turbine technology far surpassed water wheels. When the Ralston Cider Mill was converted from a grist mill around 1910, the wooden water wheel was replaced with a Stowe Turbine, manufactured in Newark, New Jersey. The mill’s water trough was replaced with a concrete headrace leading directly to the turbine casing. The turbine powered the mill’s main vertical shaft, and a control wheel on the pressing floor allowed the operator to control the speed. Today the turbine can still be viewed in the wheel pit on the lower level of the mill.

Conveyor

A wooden case with slats and metal “link belting” connects the apple bin in the driveway outside to the grater on mill’s top floor. Apples are washed and raked onto the conveyor, where they are carried up to become pomace. Once the conveyor drops the apples on the top floor, gravity assists the remainder of the cider-making process.

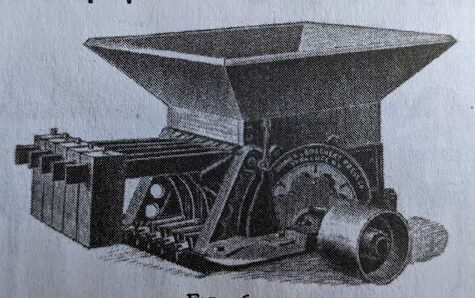

Apple Grater

In addition to cider presses Boomer & Boschert Press Co. produced other cider-making equipment, such as racks, carts, pomace chutes, conveyors, graters, pumps, and hoses. The high-speed rotary apple grater in the mill’s upper level grates whole apples into pomace, which is then pressed for cider. In an 1894 testimonial, New Jersey cider maker Walling & Cook of Tinton Falls wrote “having used your press for the past seven years with perfect satisfaction, we put in another last season and they are far superior to anything we have ever seen. Your Grater is the finest in the world. We ground three hundred bushels in 32 minutes.”

Meyer U.S. Standard Scale

Carts or trucks of apples brought to the mill were weighed on a platform scale outside the scale room of the miller’s house. The empty carts would be re-weighed afterward so the weight of their delivery could be determined. When the miller’s house burned down in the late 1930s, the wood and metal scale was the only piece to survive. It is on display in the mill. F. Meyer’s U.S. Standard Scale Company, established in Newark in 1867, gave that city a reputation for producing high-quality measuring equipment. With products ranging from small assay scales to railroad track scales, Meyer manufactured scales for the U.S. Mint and had overseas orders in South America and Cuba. He had a showroom at 27 Park Row in New York, and employed 16 people at his Newark factory.

Vats

Large vats held fresh cider, hard cider, and applejack at the Ralston Cider Mill. There are four cypress wood vats in the mill, the largest having a capacity of 7,500 gallons. In the exterior vat shed, there were three additional vats. The vats were connected with hoses and pumps. The number and size of these vats indicates how much cider and applejack could be produced at the mill at a given time.

Bonded Storehouse, or “Lincoln House”

The Ralston Cider Mill’s vat house may have been a bonded storehouse, locally referred to as “Lincoln Houses,” where spirits were aged under lock and key and closely monitored by government officials for taxation purposes. Government seals had a portrait of Abraham Lincoln. Tax collectors would use hydrometers to accurately measure the proof of a distilled product in order to assess the appropriate tax. Tours of the Ralston Cider Mill include displays on alcohol taxation and the role facilities like the Ralston Cider Mill played in the 19th and 20th century’s economy.

Grist Mill

Water Wheel

The Ralston Cider Mill was originally constructed in the 1840s as a gristmill. Water was diverted from the Burnett Brook to a mill pond on the north side of Rt. 24, and then run underground into the mill’s lower level. The “head” – the difference in height between the water source and the wheel, was 21 feet. Inside the mill, water spilled from a water box onto a 16-foot breast wheel. Turning several times per minute, the wheel produced 18 horse power to turn three grindstones on the floor above. After leaving the wheel, water exited the mill through the tailrace and re-joined the Burnett Brook. The interior water wheel allowed for grain to be ground year-round, even when the stream surface was frozen. Today, all that exists from the water wheel is the wooden axle, which can be seen on visits to the lower level.

Oliver Evans Mill Design

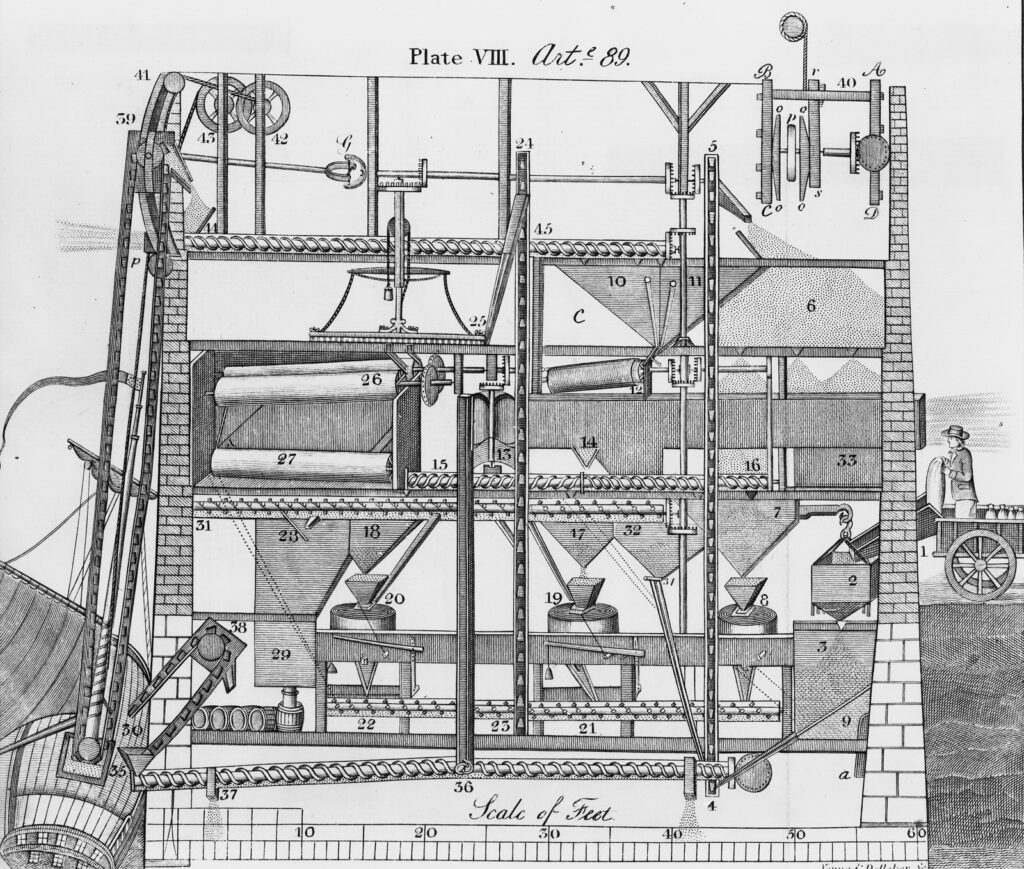

In the late 18th century, American inventor Oliver Evans developed grist mill technology that allowed an entire mill to run automatically. One miller could operate the conveyors, elevators, weighing scales, and grind stones simultaneously. “Labour was required only to set the mill in motion; power was supplied by waterwheels, and grain was fed in at one end, passed by a system of conveyors and chutes through the stages of milling and refining, and emerged at the other end as finished flour. The system, which reduced costs by 50 percent.” Evans’ design was widely implemented across the United States in the 19th century, and it is likely that John Ralston Nesbitt, the original owner and operator of the mill, employed Evans’ designs. There are still remnants of the 19th century gristmill machinery that can be spotted in the mill today.

Hurst Frame

Gristmill grindstones turn horizontally and create considerable horizontal vibrations. Structures with stone and mortar construction like the Ralston Cider Mill are not suitable for handling such horizontal vibration. Consequently, a wooden frame sitting on stone pillars holds the grindstones. This “hurst frame” is designed to convert the grindstones’ vibrations from horizontal to vertical. The stone pillars, with their high compression strength, can easily handle the force of the mill’s operation. In the Ralston Cider Mill the hurst frame is clearly visible and now holds the cider presses and pressing floor, which rests on pillars independent of the mill’s outer walls.

French Buhrstone

Grindstones for making flour from grain are found all around the world. One of the most prized types of stone for grinding is buhrstone, which is “the fossilized remains of an ancient ocean floor that became limestone and later quartz and flint. It was so pockmarked with holes where dead sea creatures dissolved that millers sometimes filled parts of the buhrstone with mortar. Buhrstone is conducive for grinding white flour because this relatively soft stone, with sharp edges of what had been sea shells, slices rather than crushes the wheat.” Most buhrstones for mills was quarried in the Marne Valley, outside Paris, France, though, for a period in the 19th century, were also produced in Georgia. Some pieces of Ralston Cider Mill’s original grindstones still exist, and period photos around 1920 show the stones propped against one another at the entrance of the mill’s driveway.