Cider in New Jersey

“New Jersey is the most celebrated cider making district in America.”

–Andrew Jackson Downing, Fruits and Fruit Trees of America, 1849

Prior to the Columbian Exchange, only crab apples existed in North America. Domesticated apple seeds were first brought by French Jesuits in the late sixteenth century. Native Americans later grew apples throughout the continent. Early immigrants from Europe brought with them seeds and seedling trees to grow in North America. Among these plants were apple trees. Apples and cider were common in England prior to the establishment of English colonies in North America. The English pilgrims of Plymouth colony brought young apple trees from England and planted their first apple orchards in the 1620s. Later in the 1600s, Cider production was recorded around East and West Jersey, from Perth Amboy to Burlington to Newark.

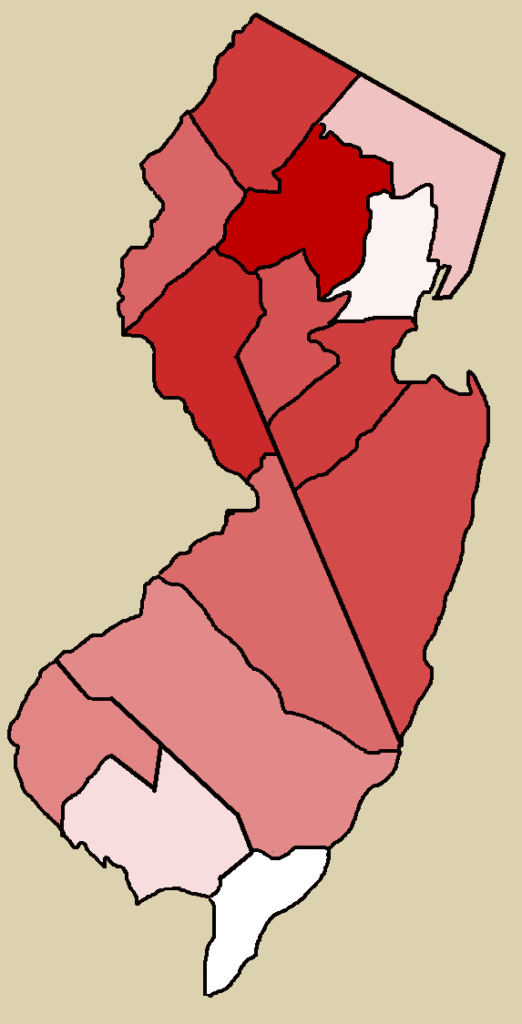

New Jersey’s climate and geography are well suited for apple cultivation. Most farms had some apple trees and a hand-operated press for turning the ripe apple fruit into cider. North Jersey in particular remained a primary apple growing and cider producing region in the United States for more than two hundred years.

Early Cider Making

In the early colonies, cider was made by pounding the apples in wooden mortars and later pressing the pomace in baskets. Hollowed out logs were also used for crushing apples. Later, a common method for grinding apples was to have a horse walk a circular grindstone around circular trough filled with fruit. Prior to industrialization, these hand- or horse-powered cider presses were ubiquitous in New Jersey. “There were cider mills scattered on plain and mountain wherever a good orchard throve.” Farmers frequently had their own press for making their cider. Early presses were often designed with a heavy beam held on wooden screws. Layers of crushed apple pomace called cheeses were made with straw. A farmer turning the screws would lower the beam and apply pressure to the cheeses, filtering the pomace through the straw and squeezing out the cider.

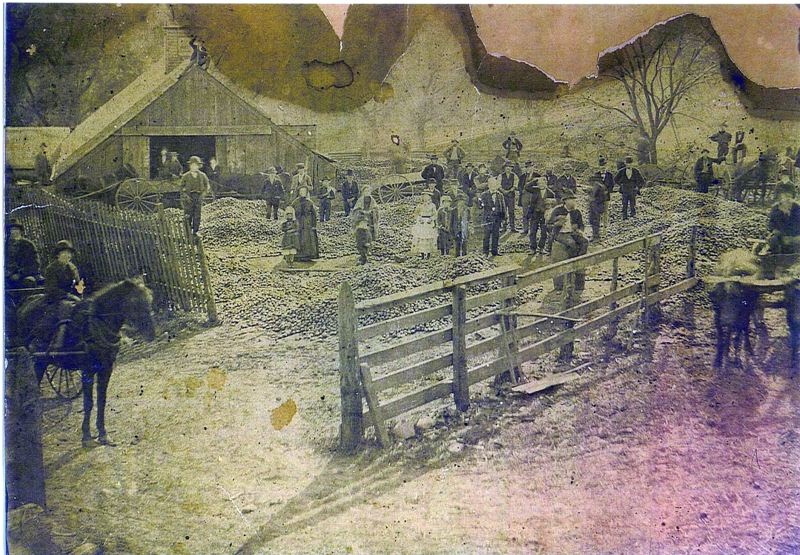

When cider presses were located indoors, in a barn or cider mill, the structure was frequently built into a slope or hillside, where apples could be delivered to the second floor and aged for a period prior to pressing on the floor below.

Industrialization

In the mid-19th century when new technology was developed to mechanize many previously hand-powered tasks, cider making machinery became available to apple producers. Improved transportation also allowed crops to be moved more easily. Though fewer mills and distilleries existed, they processed far greater quantities of cider and applejack. From being able to produce dozens or hundreds of gallons of cider a day, a farmer with a modern press could now produce thousands of gallons. Around 1865, the New Jersey Agricultural Works began marketing their “Champion Cider Press” machine and “Jersey Apple Grinder.” The company produced agricultural machinery for more than a century. Another company, Boomer & Boschert Press Co., opened in Syracuse, N.Y. in 1870. At a display in Boston in 1882, a Boomer & Boschert Co. press produced a record “1,225 gallons of cider in one hour and fifty-seven minutes from 264 bushels of apples.” Many large cider mills used Boomer & Boschert equipment at the turn of the 20th century, including Ralston Cider Mill.

Newark Cider

Orchards were common in North Jersey by the late 17th century. Renowned in particular was cider produced in Newark and the surrounding towns of Bloomfield, Montclair, Irvington, the Oranges, Elizabeth, Hillside, and Union. “They had large orchards of apples for making cider, which under the name of ‘Newark Cider’ was known over a large extent of the country, shipped to the South as well as to points in these parts. It was celebrated as the best.” Newark cider was made primarily from Harrison and Canfield apples, as well as the Granniwinkle and Povershon varieties.

Applejack

With apple orchards blanketing the state, and hand powered cider presses a common sight on most farms, New Jersey in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries found itself awash in “an ocean of apple juice.” In an era of bad roads and before electric refrigeration, finding ways to preserve harvested crops was an essential part of farming. For fruits and grains, one primary method was fermentation and distillation. It was also practical to take a large crop of fresh apples and distill it into easily stored, handled, and shipped bottles of distilled product. Early stills were crude, small, and generally only used for a small portion of the year. While some copper stills were likely manufactured in New Jersey, most likely came from Philadelphia, New York City, or England. The earliest record of a distillery in America was in Boston in 1654. In 1731 a farm for sale in Newark, New Jersey, was advertised and the notice said: “there is a good bearing young orchard and a good barn, as also a distilling house, with stills and all conveniences for distilling strong liquors and especially of Syder; and where the buyer may also be instructed in the art of distilling.” Distilled hard cider, called interchangeably cider brandy, cider spirits, apple brandy, applejack, apple whiskey, and also nicknamed “Jersey lightning,” was an important product in New Jersey’s economy. It is recorded that “George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Abraham Lincoln, George Fox and other personages either made, drank, or sold apple brandy or did all three or expressed themselves upon the merits of it.”

Professor Andrew D. Mellick, Jr. wrote: “In the middle states during the last quarter of the 18th century, many new devices arose for concocting stimulants. In New Jersey, the most important of these innovations was the pro duction of applejack from apple pulp and the distilling of cider-brandy from cider. Peaches too were converted into a sweet rich brandy. Cherry brandy was also made and plums, persimmons and pears were used. In Somerset and Morris counties applejack sprang into favor at once. Morris soon became the banner county in the production of applejack.” Applejack was a popular drink, and bottles or barrels of applejack could also be used as currency to trade for goods. For instance, farmers bringing their fresh crop of apples to a mill or distillery could expect payment in the form of bottled applejack.

19th Century: New Jersey’s Cider and Applejack Heyday

In 1810, tax records show more than 1.1 million gallons of spirits distilled in New Jersey, with an estimated three quarters of it coming from apples. In 1813 it was written that apple spirits had become such a great business in New Jersey that stills upward of 1,000 gallons in capacity were constructed for its manufacture. In 1830, there were 388 applejack distilleries recorded in New Jersey, which statewide had a population of only 320,000 people at the time. These stills existed mostly on farms where the owners distilled the cider from their own fruit. Hunterdon County was home to the most distilleries with 58, followed by Morris with 53. Applejack was a common drink in homes and at taverns around the state.Distillers advertised their products in newspapers and elsewhere. A testimonial praising Succasunna applejack distiller D. Bryant read “He is 72-years old; his flesh is firm; his cheeks are ruddy with a tinge of health and good blood… Lifting a 100-weight boulder into place, he then walks to the fence corner and picks up a two-quart jug from which he takes a long pull. That’s Apple Jack …!”

New Jersey’s applejack production supported other industries as well. Stoneware potteries made ceramic jugs, and glassmaking factories in South Jersey produced bottles. Coopers required wood and metal for making barrels.

Applejack production reached its peak in New Jersey from the 1870s to the 1890s. In 1904 the Jersey City News reported that the applejack production in New Jersey would likely reach 1 million gallons that year.

Taxation

Taxation played a vital role in the rise and fall of New Jersey’s apple industry. The first federal tax on liquor was created in 1791, during the presidency of George Washington. Enforcement of this tax in western Pennsylvania instigated the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794. The amount of tax on every gallon of alcohol produced and sold varied over time. During times of war, the tax was often increased to fund the military. During the Civil War, the tax per gallon of distilled spirit was raised from 20¢ to 60¢, then to $1.50 and ultimately $2.00 in 1865. Likewise, during World War 1 the tax was nearly tripled from $1.10 to $3.20.

Government agents were responsible for scrupulously overseeing distilled product in order to be sure that all the appropriate tax was paid. Aging liquor was kept in store houses with government locks, and monitored closely. Prior to Prohibition, as much as 1/3 of Federal revenues were drawn from liquor taxes. The ratification of the 16th Amendment of the Constitution in 1913 allowed Congress to tax individual incomes, and offset the loss of revenue that resulted from the 18th Amendment in 1920, when alcohol was outlawed.

Prohibition

New Jersey’s legal applejack industry met its demise even before Prohibition. In 1917, Congress mandated the end of fruit and grain distillation as part of World War 1 food production control laws. After years of decline, there were only sixteen applejack distilleries still operating in New Jersey at the time (ten in North Jersey, six in South Jersey). Thomas Loughlin’s Tiger Applejack Distillery at Ralston Cider Mill was one of them.

When Prohibition went into effect in 1920, it touched off a new era of illicit alcoholic production in New Jersey and across the United States. New Jersey, with its long coastline, large ports, and proximity to major cities, was a hub of rumrunning and bootlegging. At Ralston Cider Mill, the distilling and bottling operations were moved underground into hidden basements. Illegal applejack produced at the mill supplied speakeasies in Newark and New York, as well as locally.

New Jersey was the last state to ratify the 18th Amendment. And while Prohibition was never popular in New Jersey, as shown in Edward I. Edwards’ 1919 “applejack campaign,” where he was elected Governor promising to make New Jersey “as wet as the Atlantic Ocean,” it was still enforced by federal, state, and local officials. Applejack was popular during prohibition, “apparently due to its purity, real or imagined, and because of its safety in comparison with other bootleg beverages.”

Over the 14 years of Prohibition, approximately 2,000 stills were raided in New Jersey, and police confiscated property valued at $8,669,329. New Jersey recorded 4,768 arrests for violations involving manufacture, sale, possession, and transportation of alcohol. It is estimated that some 400 of these arrests directly related to applejack.

After Prohibition

In the decade after 1933, when Prohibition ended, more than two dozen applejack distilleries opened in New Jersey. Nearly all of them closed within a few years. Over time, it became increasingly difficult to make a product that could be priced competitively. In Cider, authors Annie Proulx and Lew Nichols paraphrase Harry B. Weiss’ 1954 History of Applejack: “Grains return a far greater alcohol volume for volume at a considerably less cost than apples. The Weiss equation holds that two bushels of sound apples are needed to make one gallon of 50 percent apple alcohol, while the same quantity of rye or other grains will return three gallons of 50 percent, or 100 proof, and corn three and a half gallons with similar strength. Since good apples cost more than grain, pure apple brandy is noncompetitive with grain spirits.” By the middle of the 20th century, hard cider and applejack production in New Jersey was almost extinct. Some mills, like Ralston Cider Mill, produced apple cider vinegar before eventually closing altogether.

Decline in the 20th Century

In the late 19th century, hard cider and applejack began to decline in profitability. Grain alcohols could be produced far more cheaply and with less labor, and cultivating apple orchards became unprofitable for farmers in New Jersey.

Over the course of the 20th century, the value of land for development began to exceed its value for farming, and many farms disappeared into New Jersey’s ever-growing suburbia. From 2.84 million acres of in 1900 and 1.7 million acres in 1950, New Jersey’s farmland declined to 734,000 acres in 2012. Many cider mills, like the Ralston Cider Mill, closed for business either before or after prohibition. Sweet cider was still available from orchards and small cider mills, but a number of factors contributed to the near disappearance of hard cider and applejack production.

Sweet Cider, Hard Cider and Applejack Today

From its historic low in 2012, New Jersey’s farmland acreage has grown slightly in the last decade. In From 2012 to 2017, New Jersey farmland grew by 3%. Altogether there are dozens of orchards, cideries, and distilleries growing and producing apple products in New Jersey today. Amid a revival of interest in apples and cider nationwide, the number of producers in New Jersey has grown considerably in recent years. For four centuries, New Jersey farmers and cider makers have continued their craft. By stopping at a farm for some fresh apples, or taking a glass of sweet or hard cider, or stopping by for a visit to the Ralston Cider Mill, you too can be a part New Jersey’s apple revival. Visit our Apple Map of New Jersey to discover your next apple destination.